|

McCloud River Lumber Company:

Donkey Logging |

|

|

|

As noted in the front page of this section John Dolbeer of Eureka is credited with inventing the steam donkey, mostly because he was the first to file patents on the

technology. The donkey in its most basic form consisted of a vertical boiler generating steam that powered a capstan drum, all mounted on a heavy wood sled. Similar machines had been in use for a century

or more before this date, usually as hoisting engines in mining, loading and unloading cargo, and other similar applications, and Dolbeer adapted the technologies to draw logs overland. In contrast to horse

and high wheel logging, the donkey would remain stationary at the landing and would draw logs in from the surrounding logging area. The technology advanced rapidly; early models required animals to draw the

cable back out into the woods each time a log would be brought into the landing, but additional drums quickly allowed donkeys to be equipped with haulback lines that formed a continuous loop with the main

haul line, and once a log had been brought into the landing the cable would be pulled back out to the woods by that haulback line. Once an area had been logged the donkey would move to the next setting,

either by dragging itself overland using its own cables or by flatcar for longer moves. The McCloud River Lumber Company used donkeys from the beginning, mostly in rougher terrain settings that could not be efficiantly logged with the horses and high wheels. The company used the donkeys to yard logs in from up to 440 yards out from the landing. In 1910 the lumber company started equipping its donkeys with A-frame loading booms off the front end of the machines, which allowed them when placed perpendicular to the tracks to both yard the logs into the landing and then load them onto the log flats. Donkeys completely replaced the horses and high wheels by around 1920. The McCloud donkey logging hit its peak form in 1925 with several modifications effected to its machines and operating practices, namely (1) equipping the donkeys with separate loading machines, (2) shortening yarding distance from 1,320 feet (440 yards) to no more than 1,000 feet, and (3) increasing log lengths yarded out of the woods from 16 to 32 feet. Taken together these changes increased daily average output for each donkey engine from 40,000 board feet to 65,000 board feet, with some machines recording up to 90,000 board feet. Each donkey engine during this time was operated by a crew of 18 men. This high water mark for donkey logging only lasted about three years, as by 1928 they had been completely replaced by tractors. |

|

|

|

|

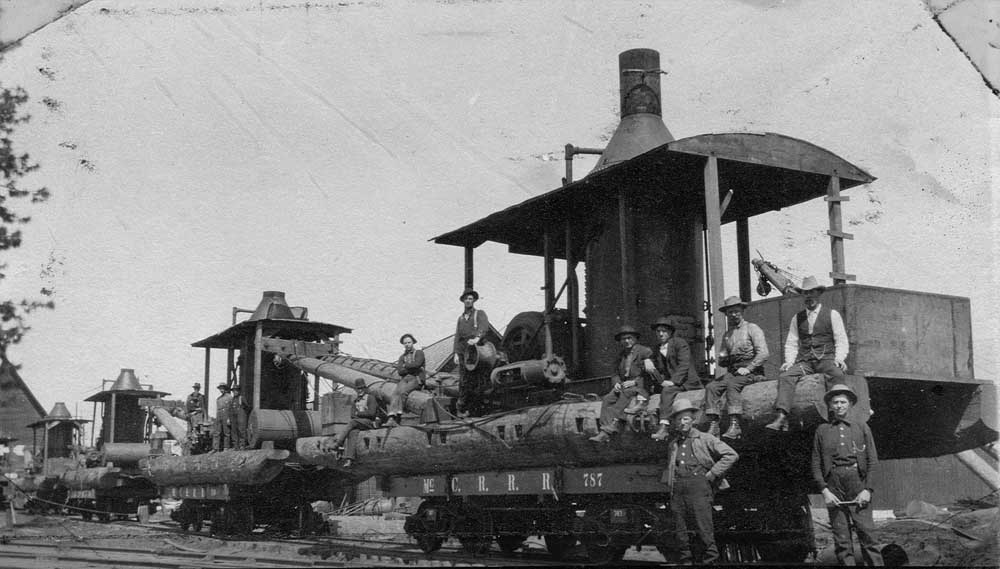

An early steam donkey and its crew somewhere in the Mt. Shasta region. Miller photo, Kuhlman collection, courtesy Martin Morisette.

|

|

|

|

|

Another early donkey in the McCloud woods. Heritage Junction Museum.

|

|

|

|

|

A good example of a later donkey engine, this one from around 1910. The increasing size and complexity of these machines is easily seen when compared to the photo above. Heritage Junction Museum.

|

|

|

|

|

Three donkey engines and a McGiffert loader parked next to the original railroad shop facilities next to the old mill in McCloud. Heritage Junction Museum.

|

|

|

|

|

Four donkey engines equipped with the loading booms on flatcars and ready for shipment to the woods. Heritage Junction Museum.

|

|

|

|

|

A donkey set up to yard and load 32-foot logs. The railroad's log car fleet was still mostly 26- and 28- foot flatcars at the time of the change, and until the company could rebuild the short

cars to 40-foot length and purchase newer cars the lumber company loaded the longer logs across two of the shorter flats, as seen here. Heritage Junction Museum.

|

|

|

|

|

The lumber company scrapped out its donkey engines after the conversion to tractor logging, mostly at the first Pondosa camp though a few remained intact long enough to be moved with the camp. McCloud's

last remaining donkey engines are seen here in New Pondosa about 1937. Roland Edwards collection, courtesy Marilyn Rountree.

|

|

|

|

|

One last shot of one of the last donkeys awaiting the scrapper's torch in Pondosa. Roland Edwards collection, courtesy Marilyn Rountree.

|

|

|